On Art, Multiculturalism, and Motherhood

“Sometimes I get shivers thinking, ‘What if I hadn’t found my art?’” says sculptor Marie Khouri, sitting among dozens of pieces of her artwork in her home in Vancouver’s Southlands. “Who would I be without it? When I look back, I feel like I was an empty shell that needed filling up with this knowledge.” The petite tour de force sweeps a hand around her living room, which is dotted with her hugely varied works of art. A sculptural wooden wine rack rests upon the kitchen counter nearby circular bronze-cast candleholders; behind a voluptuous wooden cocoon chair there is a wall hanging studded with chunks of charcoal to mimic the topography of Lebanon.

Tucked away in the basement of her home is her “thinking tank” studio—the air rich with the innocuous scent of melted wax—brimming with small clay prototypes, weaving samples, and a monolithic work-in-progress: a wax-coated panel that will soon be cast in bronze and installed in a Hong Kong hotel as a room divider. Upstairs, a cozy room devoted to her jewellery-making is like a gilded mecca laden with 24-karat-gold-covered cuffs, abstract scorpion pendants, and fuzzy purses with ornate clasps. All of these are her own designs, crafted by her own two hands. If there are any limits to Khouri’s artistic world you’d be hard-pressed to find proof, but her life hasn’t always been so beautiful.

Born in Egypt and raised in Lebanon, Khouri’s father was assassinated during the Lebanese Civil War, and her mother moved Marie and her brother to Vancouver in 1975 to escape it. Khouri soon found her way to Paris, where she lived with her husband, had her three children, and took art courses at L’Ecole de Louvre; at the age of 35, she picked up her first piece of clay. A Vancouver resident for the past 15 years, Khouri has built out her career to include trademark large-scale pieces of sculptural art carved in marble, concrete, and Styrofoam, or cast in bronze. Most of these gargantuan sculptures began as tiny clay palm-of-your-hand prototypes, then were carved by Khouri with the help of various teams around the Lower Mainland, and the world, depending on their final destination.

Vancouverites will have seen her pieces in a handful of different places, including two mirrored stainless steel sculptures installed in the Olympic Village called Eyes on the Street (2018), or the flock of abstract white doves she created for the lobby of the acute care centre of B.C’s Children’s Hospital. Another notable work, displayed five years ago at Equinox Gallery, is a 75-foot-long seating arrangement of flowing white benches called Let’s Sit and Talk (2014). The project’s 15 separate pieces—which spell out the title in Arabic script—were painstakingly carved with the help of an assistant from polystyrene foam, sprayed with fibreglass-infused resin, then sanded to their final lustre. Khouri, not one to be overwhelmed by any project, is currently working on a Hebrew version of those benches, which function as a way for her to make peace with the past while also opening a gateway to conversation between different communities in the present. Therein lies an inherent beauty of her work: there is always more than meets the eye. And we don’t want to look away.

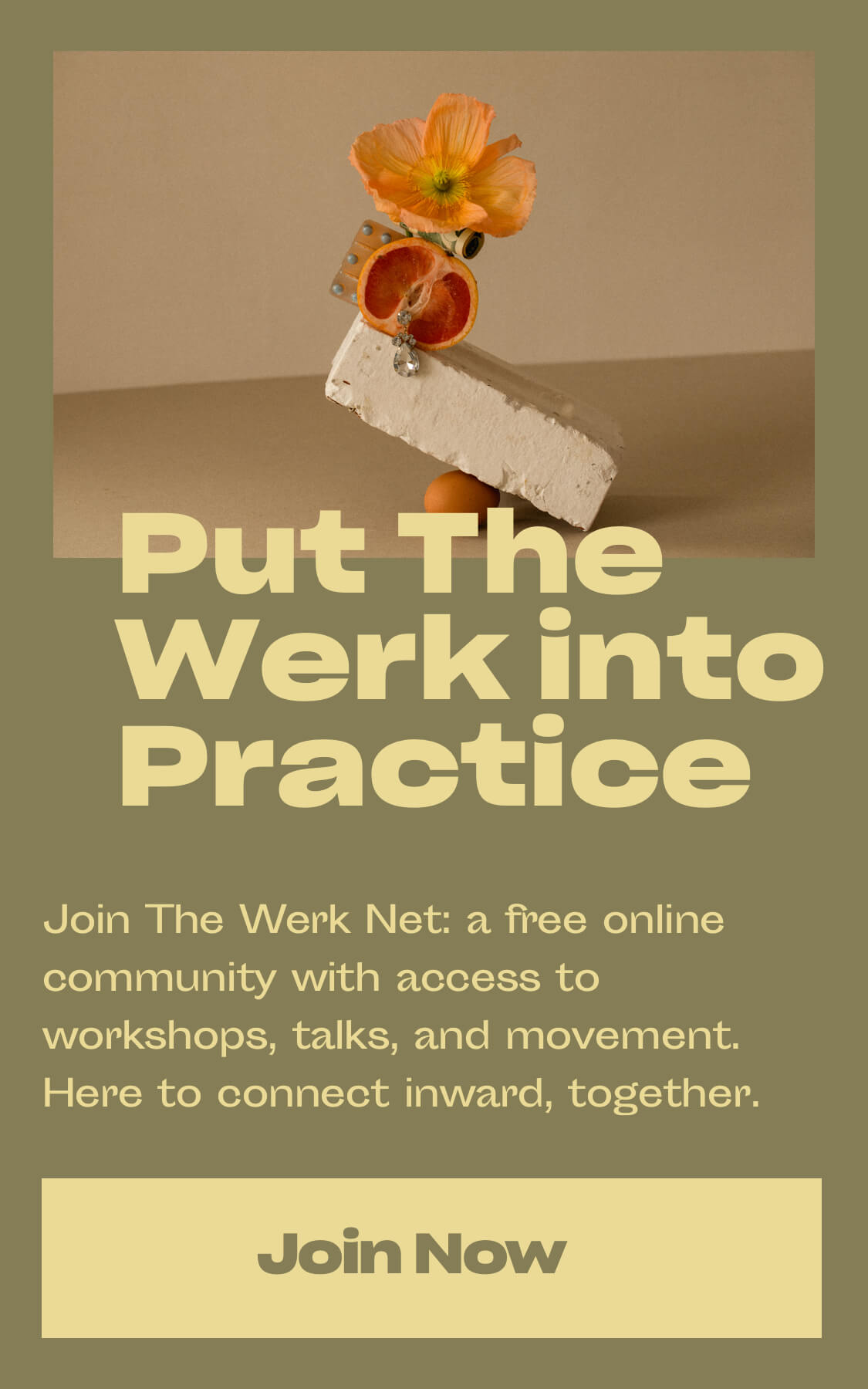

Image by Ema Peter

These days you live and breathe your art, but this wasn’t always the case. How and when did you discover your calling?

I was 35 years old when I started sculpting. And to me that is very important, because a lot of time people feel that when they are 25 or 30, they have got their paths, they have done that, and it’s too late to do something different. It is never too late. It is only too late when you are dead. Regardless of where you start, once you get a few years in you are already at another level. And for me, I found my voice. I don’t care now about what I am buying, wearing, what I look like… all of this is superfluous. What is meaningful to me now is what I am doing.

You speak five languages, used to be an interpreter, and incorporate language into some of your artwork. What is your relationship to language today?

Language has always been with me, and it came very easily to me. My mother is Spanish, my grandmother is Italian, I was born in Egypt, raised in Lebanon. Then we moved to Canada, and I lived in France most of my life. So, for me, if you speak two languages you are two people. If you speak three you are three. Because speaking it is not only about the language itself—no. In some ways you define a culture, an area, a place, a geographical spacing. So, if you speak Italian you have a link to the music, the humour, the food, the smells of that culture. It’s as if you behave a little bit differently, too—you become another edition of yourself.

When you are creatively blocked, how do you move forward?

I am terrified of the white page, so I constantly have different things on the go with different materials, and I move between them all the time. That way you constantly evolving with that material. Also, I am a scavenger… Stuff on the street that is like garbage to some, it is not garbage to me. I collect the interesting things that I find—organic elements, or the most beautiful things on the floor of a metal shop—because they take me somewhere else.

Tell me about your days attending L’Ecole du Louvre in Paris—it all sounds very romantic. How did that experience push forward your artistic path?

I originally wanted to take drawing, but it was frustrating, because I had all these ideas in my head but they didn’t come out [on the page]. The teacher said to me, “The way you draw, you would be happy in sculpting.” So, she took me three doors down to a clay sculpting class. They asked me to do one exercise, and asked me, “How long have you been sculpting for?” And I said, “Never.” That was the beginning of something. Early on, the teacher told me, “When I went down to the kiln, I recognized your sculptures. This is the first time I have had a student that never touched [any clay before] and has this in her.”

You moved to Canada 15 years ago. How has making your home here affected your art?

Organic. All of my work now is textured, so organic, and that is from living here. I’m very, very urban, you see—I’ve lived in Cairo, Lebanon, Paris, Madrid—and in all those places, you had to go to a park to see greenery. Coming here I was overwhelmed at first [by the rain] but then, little by little, nature started almost coming into my veins.

You make artwork all over the world. How many pieces are you working on right now?

A lot. I have a piece in Italy being made in marble, I have three different pieces of work for three different clients in the foundry, I have benches that are being done for Miami in Styrofoam. Next week I will spend one day at the foundry, one at the place with the Styrofoam project, one day talking with Italy for a project that is being carved. I need to work on different things because I find that every time I move onto something, I have a new eye on it. If I am working on one thing all the time, I tend to just drown in it—I do not see it anymore.

You have navigated raising three children while building a successful career along the way. What is your approach and ethos towards motherhood?

I am a big believer that it is not the quantity of time you give a child, but the quality. If I am working, regardless of the day I have had, I come home, I hang my working hat at the door, and I become a mother. Another thing I have always tried to do is cook dinner. I think it is the nicest part of the day, where everyone reunites—this is also a time where difficulties come out. I also find [as a working mother], if you’re happy, and you’re evolving, your kids can see you grow as a woman who has built a career for herself. They see you work hard, and struggle—that is important. I also feel that today we as women have a place we never had before, a chance to make a difference, and we are really pushing the boundaries that were previously manly boundaries. As a sculptor, I face men all the time—it’s a tough job, it is very physical—and to make yourself a place in this kind of field, you have to be very tough to go out there and get what you want.

Image by Ema Peter

What does wellness mean to you and how do you “stay well”?

Today, my wellbeing comes from my work. Of course, family comes first, but when they are all doing well it comes from my work. My work is what feeds my soul, and it has taken me to travel and meet so many people. A few years ago I did a piece in marble [overseas] and stayed with the group I was working with; we would eat lunch together, full of dust in our eyes and our masks, then eat dinner together after the working day. Those were some of the most intense moments that I have lived with human beings that I did not know existed years before. So, you create these links with people through your work. Now, every time I look at a piece of marble, I think of the person who helped me carve it. They are all so full of memories and life—they are carriers of moments.

Who have been your life’s great teachers, or inspirations?

My father in law, for the aesthetic he brought to me, is one. He was an architect, and I came from a very different background, so I really listened when he spoke of things like forms, shapes, buildings. Also, my mother. She is 85 now and has lived here more than half her life, but she had a very tough life. She lived through Franco and the Spanish Civil War, then the Middle East, and my father’s death, then coming here with two children without speaking the language; she saved us from where we were. Also, I was a kind of artist-in-residence at Capilano College when George Rammell was the head of the sculpture department. He said, “What do you want to work on this term?” And I said, “How big can I go?” And he said, “Well, how big do you want?” And that’s really how I started creating public art. Because, back in Paris when I was studying at the Louvre we had shelves to store our work, so the sculptures couldn’t be bigger than the shelves.

What artists have informed and inspired your work?

I discovered sculpture when I saw Henry Moore’s work. What I love about sculpture is that you can touch it, and you can smell—the wax, the bronze, the smell of metal. And all of my work is to be touched, I am not sacrosanct—on the contrary. I make things that people sit on, pieces that have to live with us. They are part of you, part of your house, your eyes share it, your body can share it. I love that Bill Reid sculpture at the airport [Spirit of Haida Gwaii], where people touch it. Everywhere is green, but where people touch it is gold—how beautiful is that?

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This post is tagged as:

You may also like...

The Latest

People & Places

How Ara Katz is Redefining “Self-Care” as Rooted in Science with Seed

The co-founder, mother, and self-proclaimed serial entrepreneur unpacks her philosophy on what it means to be well. Ara Katz hates the word “success”. Not because of its listed definition in a di...

Do Good Werk

9 Passive-Aggressive Email Phrases That Are Basically Evil

A Rosetta Stone for every time you want to :’).

Woo Woo

Get to Know Your Astrological Birth Chart

How to find meaning in the stars — and what it means for you.

People & Places

The 5 Best Places In New York To Meet Your Next Investor

Where to rub shoulders with the city's movers and shakers.

Do Good Werk

10 Unhealthy Thoughts You Convince Yourself Are True as a Freelancer

If you work alone, you might be particularly susceptible to distorted thoughts that hurt your mental health.

People & Places

Creating a Conference-Meets-Summer-Camp for Adult Creatives

An interview with Likeminds founders Rachael Yaeger and Zach Pollakoff This past September, I sat in front of an obituary I wrote for myself after a session with a death doula. No, I didn’t know w...

People & Places

When Something Golde Stays: An Interview with Golde’s Co-CEOs

“For us it was never a question,” says Issey Kobori, speaking of the decision to build a business with his partner Trinity Mouzon Wofford. At just shy of 27, Kobori and Wofford have secured a host ...

Better Yourself

Are They Toxic? Or Are They Human?

There’s a difference between putting up boundaries and putting up walls, and the latter is what breaks relationships.

Do Good Werk

How To Combat Seasonal Affective Disorder At Work

Here’s what to do if seasonal affective disorder starts to take a toll at the office.

People & Places

Reclaiming Womxn's Wellness Spaces from a White-Dominated World

How The Villij built a collective that their community can connect to.